I write about my history with my body with the same edge that ex-lovers reluctantly speak about each other in hushed voices over strong drinks.

My body and I, yeah, we have a history. It is not an obvious history in the sense that I have a history of living and breathing and waking up everyday. That’s true, but it’s more than that.

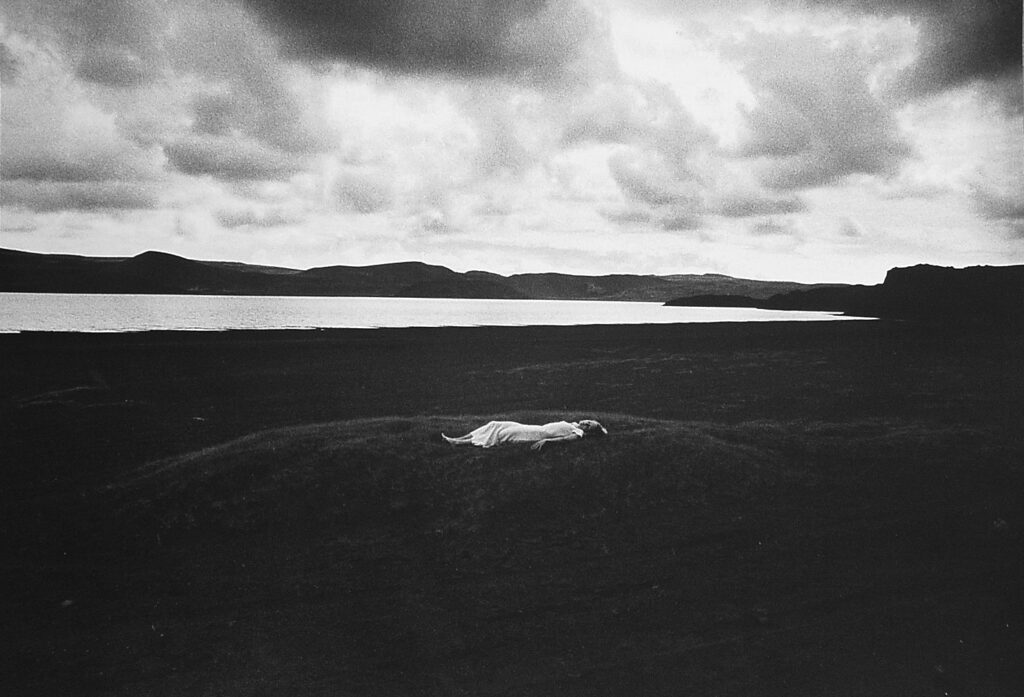

My history with my body is adversarial, existing on a spectrum marked by my birth, near death, and the fact that I lived to write about how I’m still alive.

At the time of this writing, it is National Eating Disorder Awareness Week, and I am here to tell you about what it means for me, as a woman, to be alive.

My eating disorder began in late 2000 when I was twelve. I loved fashion magazines and thought every woman was supposed to look like a coat hanger draped in haute couture. As an Armenian Ashkenazi Jew, I was never petite. I ate hamantaschen during Purim and was essentially raised on spaghetti and matzoh brei. Since nothing in my genes branded me with being naturally thin, I decided to make myself that way.

In the spring of 2001, my heart stopped after having an anorexia-related seizure. The time after was a dizzying array of doctors, hospitals and state mandated treatment programs. In all the years that medically qualified professionals tried to treat me, not once did any of them acknowledge how society’s narrow appreciation for women contributed to the war we wage against our own bodies.

The closest I ever came to having that thought validated was by an EMT who felt bad for me because he “saw this stuff all the time.” Treatment left me feeling isolated and wondering what I had done to myself rather than what society had done to women in general. In a world that devalues body diversity, it is no surprise that my story is not rare.

Hating my body took years off my life. I lived in blocks of time, oscillating between self love and self hate; the times when I hated my body and wanted to give up, and the times when I felt I could feel something else for it.

Had I loved my body when I was 21, I may have danced more. I may have been more adventurous and bold. I may have worn shorts more often or crop tops in the summer. Anorexia made my life in hindsight feel tragic, but from this loss came a love and appreciation for my body that refused to give up on me even when I wanted it to.

Without this experience, I often think about whether I would have ever learned to love my body on my own terms, or whether I would have allowed myself to be defined by what society prescribed for me. The uncomfortable truth is that what almost killed me may have saved my life.

From the time we are born, a woman’s life is one of protest. Our diverse bodies exist in defiance of society’s expectations that our value be predicated on our dress size. Society punishes us for our imperfections by treating us as collateral, wielding our bodies as weapons against us in a war we did not begin. Why must we exist for others but not for ourselves? In a world that defines beauty on the narrowest terms, learning to love our bodies is the best kind of rebellion.

It took me years to realize this but once I did, I was able to take back my body, and my life.